Thoughts (Loosely) Based On the Graphic Novel Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands

Take a sexist workplace scenario. A situation in which men outnumber women 50 – 1. A situation that involves consistent and continual harassment of a limited number of women. A nightmare for them

Now reverse it.

Reverse the ratio of males and females.

50 women to every one man.

Could the situation be a nightmare for women, but a fantasy for men?

You’ll have to be the judge.

Whatever the answer, there is no question that Kate Beaton’s graphic novel Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands dredges up some viscous stuff. What you make of it might be determined by your gender.

Beaton is best known for her wacky absurdist hipster historical comic Hark! A Vagrant, which is often quite tangential, so I should warn you that this new memoir tackles sexual harassment, rape, environmental devastation, soul-crushing debt, and relative ethics head on.

She goes at it.

It’s a great book, and it really expanded my perspective on sexism and sexual harassment. Once again, a work of fiction taught me to walk in another person’s shoes . . . or another person’s pumps?

Stilettos?

Sling-backs?

We’re talking lady shoes here. Kate Beaton’s little shoes. Or little work boots?

Or perhaps they aren’t little!

I have no idea how big Kate Beaton’s shoes are.

But there I go again, making sexist assumptions. And I’m trying not to be sexist in this post, but it won’t be easy. Because I’m a man, and certain things HAVE been easy for me.

I haven’t had to worry about the gunk Beaton unearths in her book.

I’m a bit like Nigel Tufnel in Spinal Tap.

“What’s wrong with being sexy?”

The band’s manager, Ian Faith, corrects him: “Sexist, not sexy.”

Let me set the scene. Then I’ll reverse it.

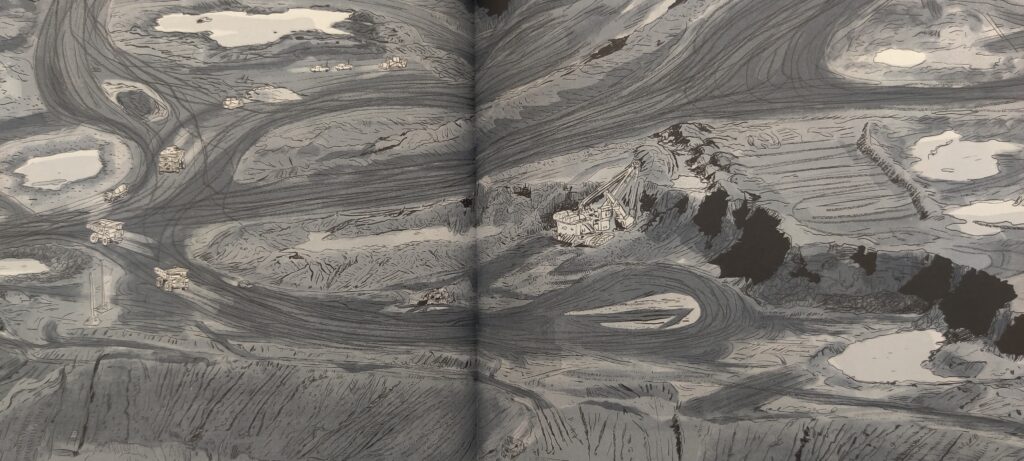

After graduating college, in 2005, Kate Beaton traveled from her home– Cape Breton, Nova Scotia– to the oil sands of Alberta. This is where they mine bitumen, the gooey low-grade oil used to make pavement.

Her mission? To pay off her student loans.

At first, she worked at a restaurant in the town near the oil field– Fort McMurray. The town is not so bad. There are women and children around. Then she got a job in the “tool crib” at Syncrude and commuted to the mine from the town. Eventually, she transfers to the Long Lake mine and lives onsite. The mine is still under construction, and though it’s more lucrative to live on site (room and board paid for) it’s also lonely and– for a young woman– a little bit scary.

According to Beaton, The ratio of males to females is 50 – 1.

It seems that this extreme male-to-female ratio is a tipping point for bad behavior. As her friend Leon, a fellow tool crib worker, points out, the men “are bored and crazy . . . they do things here they wouldn’t do at home.”

Beaton’s graphic novel certainly contains an argument for the nuclear family, for a balance of men, women, and children. That balance creates civilization.

But what fun is civilization?

Let’s head back to the oil sands. Back to Long Lake.

The “tool crib” is where the workers go to sign out various tools and equipment. Several days after Kate begins working in the tool crib at Long Lake, a line-up of men forms around the building. The men have heard the news: there’s a new woman working at the camp. So guys invent bogus reasons to visit the tool crib: several men will come and sign out the same small wrench, dudes will sign out tools they don’t need, guys will sign out gloves they already have, etc.

The men are there to check out the new female, and the are audibly commenting about her appearance and her body.

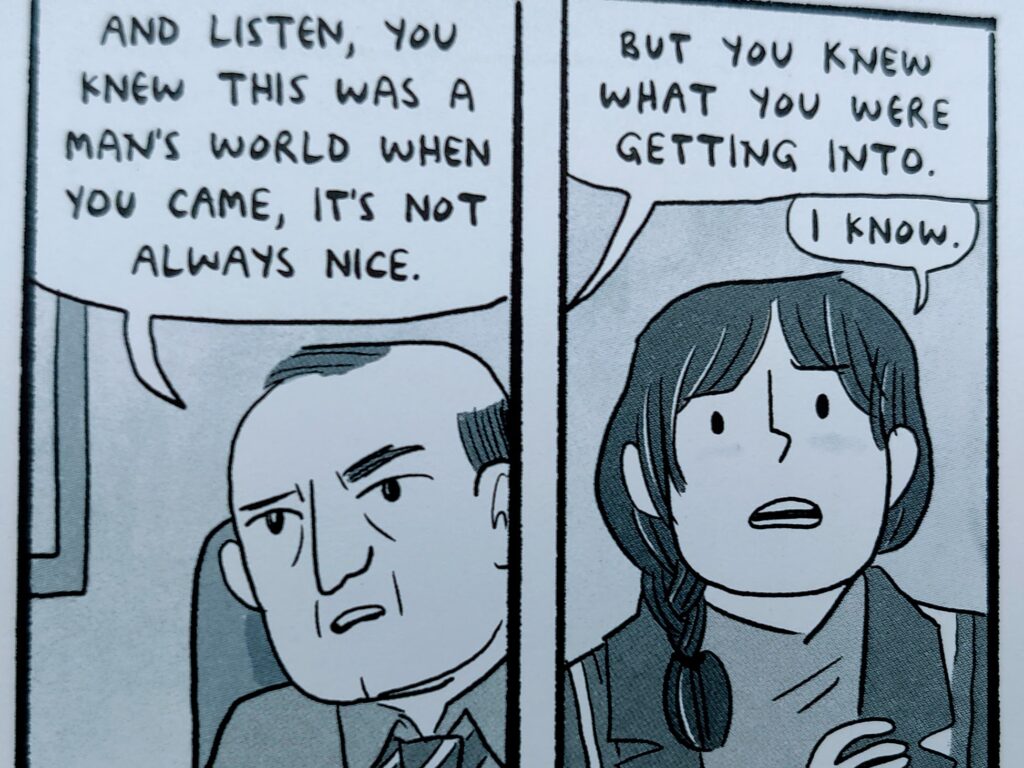

Kate complains to her boss that she’s in a fishbowl, but her boss essentially tells her to have thicker skin. He says she knows what she signed up for.

Essentially he says: YOU have to change your attitude because we can’t change the system. You have to adapt. This is a classic stance in the business world.

You may have seen Amy Cuddy’s TED Talk on the self-empowerment of “power posing.” Cuddy offers women a quick fix to combat sexism, based on confident body language.

Anand Giridharadas tells her story in Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World. He describes how Cuddy, a feminist scholar of twenty years, educated at Princeton and employed by Harvard, often examined structural and systemic issues in our society– heavy intellectual stuff– but then she transitioned from the world of academia to the big-money conference circuit. Giridharadas describes this as a transformation from a public intellectual to a thought leader.

Cuddy sincerely grapples with the costs and benefits of this change, but realizes to reach this larger, wealthier audience, she has to abandon her hope of structural change– she has to abandon attacking sexism at the roots– and instead, she has offers more digestible tweaks that offer more of a win-win scenario. That’s what big business wants.

She ends up creating one of the most-viewed TED Talks of all time. She eventually regrets simplifying the issues and promoting the idea that women can take back power with a mere stance. Power-posing seems to be a life hack for female victims in a system that will never change. It puts some power in the hands of the poser– and perhaps even changes the poser’s body chemistry, although this finding is disputed– but doesn’t really take any power away from the system. So it’s a win-win in the metaphorical universe that Giridharadas calls MarketWorld, but it’s also a more scientific, enlightened way of saying: to survive in this world, you need to have thicker skin. It may be more palatable, coming from an educated woman, but it’s the same message the boss gives Kate Beaton at Long Lake.

Suck it up and salute.

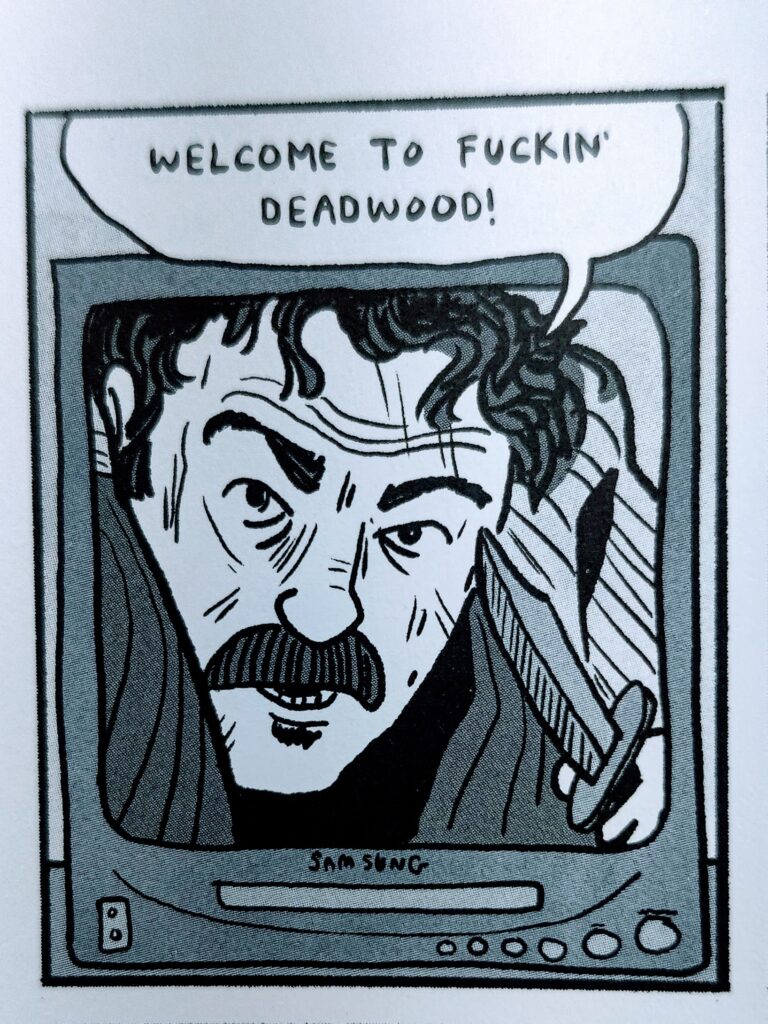

Beaton provides an especially symbolic frame for life at Long Lake. She’s sitting in her dorm room with a couple of guys she’s friends with (I believe one of them is her cousin) and they are watching Deadwood. Al Swearengen’s face fills the TV screen and the dialog bubble says, “Welcome to fucking Deadwood.”

I often miss symbolism, but even I got this one. Long Lake IS a modern version of Deadwood. Like Deadwood, it’s off the map. It’s a bit lawless. Desolate. And it’s a place full of hard-working, tough men, mainly concerned with stripping the earth of its resources. Lonely men without their families.

As Al Swearengen succinctly put it:

“Take your civilization and get the fuck out of here.

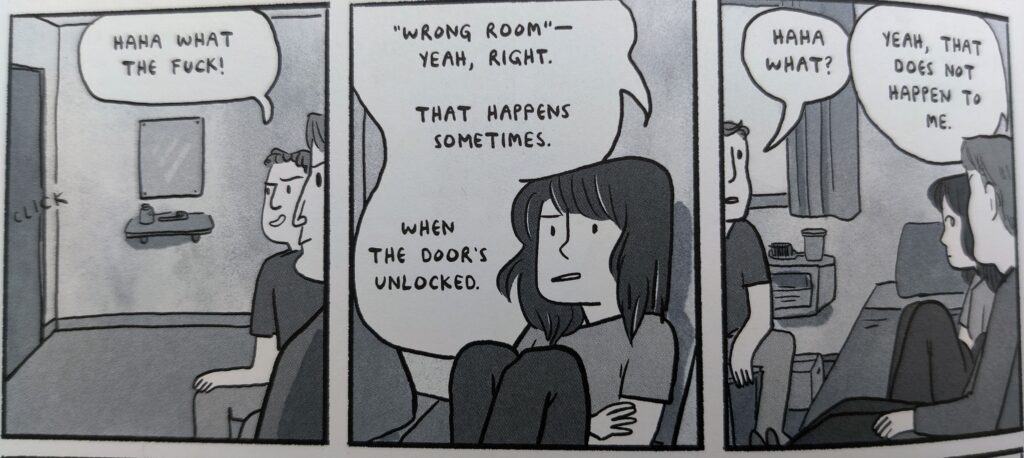

While they are watching Deadwood something weird happens. A very Canadian looking man wanders into Kate’s room, takes a peek at her, and then says, “Oops, wrong room.”

The guys are like: “What the fuck?”

Kate explains that that happens sometimes when she leaves her door unlocked– guys wander in by mistake– maybe because she’s in the middle of the trailer? The guys are like: That doesn’t happen to us.

So this is where I needed to really look at things from a female perspective.

If you asked me: a solidly built, relatively-fit, middle-aged man, how it would feel to live in a desolate location where the female-to-male ratio is 50-1, where women would line up around a building to get a look at me and comment about my body, and where horny women would occasionally barge into my room “by mistake” because they were looking to hook up, I’d say: sorry, I’m married and love my wife, but if I was single . . . sign me up!

Kate Beaton’s nightmare is a male fantasy. The barging into the room thing is the start of most porn scenes. And let’s face it, for the most part, men watch porn. There are exceptions to all these rules, of course, and gender roles are fluid– but still.

What a mess.

In some ways, I do live in the reverse world of the oil sands. I’m a male high school English teacher. In my department, I’m probably outnumbered by women 3-1. This really shifts the typical patriarchal power dynamic. My boss is a young slender, attractive young woman who wears fashionable outfits. There are a number of good-looking female English teachers. And they’re always talking about body parts– male and female. Butts and boobs and arms and calves and even dicks.

The HBO show White Lotus really got them talking about dicks.

They often comment on my nipples, which protrude through my Under Armour golf shirts when it’s cold. While I probably wouldn’t comment on their nipples, I’m fine with the reverse. It’s a humorous shift in gender norms. Maybe some guys would mind this, but I don’t– and neither do the other guys in the office. It’s not very scary to be harassed by a bunch of women.

Unless you’re a student.

I recently found out that the students are much more fearful and intimidated by the female teachers in our department. A girl was worried about getting my friend Cunnigham, who– from my perspective– is a lovely, charming, funny, and pretty thirty-something (who’s also quite pregnant).

My student, a junior girl, was like:“I don’t want to get her, she’s scary! Is there any way I could get you for College Writing next year?”

And I was like: “She’s scarier than me? You’re not scared of me? A 190-pound, well-built bald dude with hairy arms?”

And all my students were like: “You’re not scary at all!”

It was kind of emasculating.

But, honestly, it’s fun working with a bunch of women (and going to happy hour with a bunch of women). There’s no sexual harassment, instead, we have something called “sexy harassment.” Most of the time, it’s the women commenting positively on each other’s outfits and fitness achievements, but men are allowed to partake as well. It’s very civilized. It’s not sexist, it’s sexy.

So for most men, myself included, the reverse of the Long Lake encampment would be reason to celebrate, not ponder the deepest philosophical questions about morality and relative ethics.

This male fantasy is why I’m never getting a vasectomy.

Or this is reason number two.

Reason number is fairly obvious. The “Dinner Party” episode of The Office really hammered it home.

I’m not having anyone “snip snap snip snap” around my junk.

But the other reason is connected to this male fantasy of being surrounded by fecund women, the reverse of which– being surrounded by virile men– is Kate Beaton’s nightmare.

I think most guys have pondered the idea that at any moment, shit might break bad and you might be called upon to repopulate the planet.

For instance: what if there were a highly contagious virus that targets the Y chromosome and kills all the men? Or all of them except Yorick Brown and his pet monkey?

This COULD happen. It certainly happened in the post-apocalyptic sci-fi comic seriesY: The Last Man.

Absurd. Sure. But certainly a male fantasy trope.

Probably the most satirically dire demonstration of this fantasy is in Stanley Kubrick’s nuclear annihilation comedy Dr. Strangelove: Or How I Stopped Worrying and Learned to Love the Bomb.

The world is in the throes of a nuclear holocaust– ironically caused by an impotent man named General Ripper, who to assert his manhood started a shooting war with Russia– and the men in the War Room are brainstorming.

What to do? What to do?

Dr. Stranglelove — an ex-Nazi in charge of U.S. military weapons R&D — suggests that the survivors of the initial nuclear blast could hide out in “some of our deeper mineshafts.” Radioactivity wouldn’t penetrate down there and in a matter of weeks, sufficient improvements in the dwelling space could be provided.

In the plan that he proposes to President Merkin Muffley, several hundred thousand citizens would need to remain in the mine shafts until the radiation subsided: one hundred years.

Peter Sellers plays both roles.

PRESIDENT MUFFLEY: You mean, people could actually stay down there for a hundred years?

DR. STRANGELOVE: It would not be difficult Mein Fuhrer! Nuclear reactors could, heh… I’m sorry. Mr. President. Nuclear reactors could provide power almost indefinitely. Greenhouses could maintain plant life. Animals could be bred and slaughtered.

The plan then takes a more eugenic, rather sexist slant.

Dr. Strangelove suggests a computer program should be used to determine who gets selected to go down into the mine shaft (besides present company in the War Room . . . they get a free pass, of course).

And then we get to the real mission. The population in the mine shafts would have a “ratio of ten females to each male” and the women would be selected for “highly stimulating sexual characteristics,” Dr. Strangelove estimates that within twenty years the U.S. will be back to its present gross national product.

Even the highly distractible General Buck Turgidson finds this plan interesting. As does the Russian liaison.

GENERAL TURGIDSON Doctor, you mentioned the ratio of ten women to each man. Now, wouldn’t that necessitate the abandonment of the so-called monogamous sexual relationship, I mean, as far as men were concerned?

DR. STRANGELOVE Regrettably, yes. But it is, you know, a sacrifice required for the future of the human race. I hasten to add that since each man will be required to do prodigious service along these lines . . .

So yeah . . . guys. They’re always looking for a reason to “necessitate the abandonment of the so-called monogamous sexual relationship.”

Even during a nuclear holocaust, they’re actively pursuing a scenario of ten females to every one male.

These men can’t wait to do “prodigious service” for the human race. Such a sacrifice.

So this is a really important book for men to read, so they can understand and empathize with the narrator. So they can walk in Kate Beaton’s shoes for a bit and realize that when men objectify and harass women, it’s much scarier than when the same happens to men.

The graphic novel suits this theme. If this were written in prose, I’m not sure if I would have made it through. The material get repetitive and melancholy and didactic. But the simple drawings help you identify with Beaton. You become her.

Scott McCloud explains this in his meta-comic Understanding Comics. We actually identify more with comic characters that are somewhat less realistic. Think about the gang from peanuts. Or Calvin, from Calvin and Hobbes. You become that character. If the character was drawn more realistic, you’d be looking at them, rather than seeing the world through them.

Beaton also has beautiful interstitial line drawings that divide the chapters– drawings that detail the environmental devastation and the desolate beauty of where she worked.

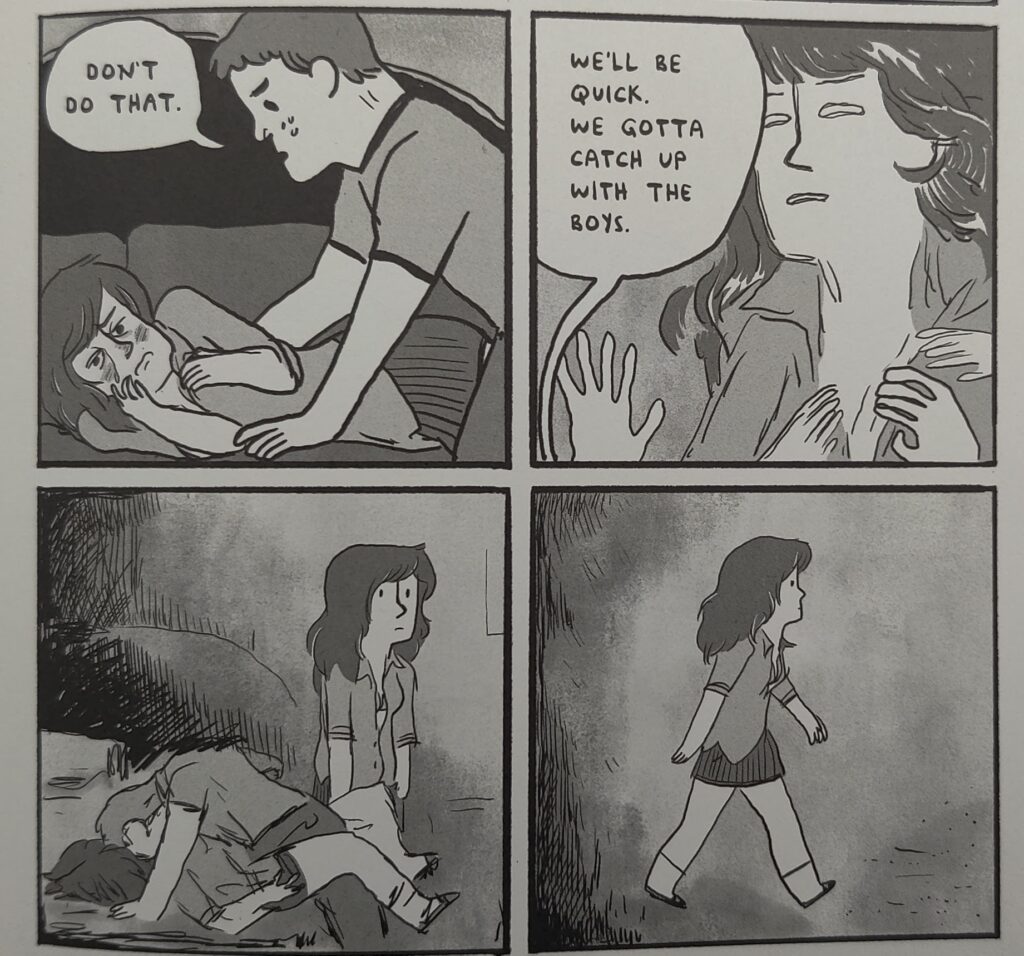

But the most powerful drawings are simple, and depict her day-to-day plight in this place. This includes a drunken rape scene.

This is how she handles it.

There are moments when the book gets profound. Beaton contemplates the accidental death of several workers . . . and contrasts this with the gory safety videos they are forced to watch. She also contemplates relative ethics. Beaton and her sister wonder if this environment would change ANY man– they wonder what would happen to their father if he lived out at the camp, away from his family. Would he drink and do drugs? Commit adultery? Harass women?

When in Deadwood, do as Al Swearengen would do.

Psychologists keep adding evidence to this idea that place is more important than person, that setting is a stronger influence than character . . . at least for most of us (Jesus and Gandhi excepted). The Stanley Milgram Shock Experiment, the Stanford Prison Experiment, the Asch Experiment– all these illustrate the power of circumstance on character.

The bromide “you are what you eat” should be amended.

You are where you live.

Or, to put it more colloquially:

“Men will live like billy goats if they are let alone.”

Charles Portis — True Grit

Kate Beaton does survive this crucible . . . and she survives it with her sense of humor intact. She pays off her college loans. She defies the odds and becomes a successful cartoonist. But there’s no question that the male behavior she witnessed frightened her, scarred her, and made her wonder about what happens to morality when there’s too many men around.

Because some men, not all men, but some men– when they are hanging out with other men– behave like this . . .

Kate Beaton understands this as well as anyone.